Professor Graham Hitchen, CRAIC, Loughborough University London

This essay summarises the outcome of a research project, run in two phases between July 2022 and February 2023, which aimed to map the emerging ecosystem of Virtual Production (VP) in the creative industries.

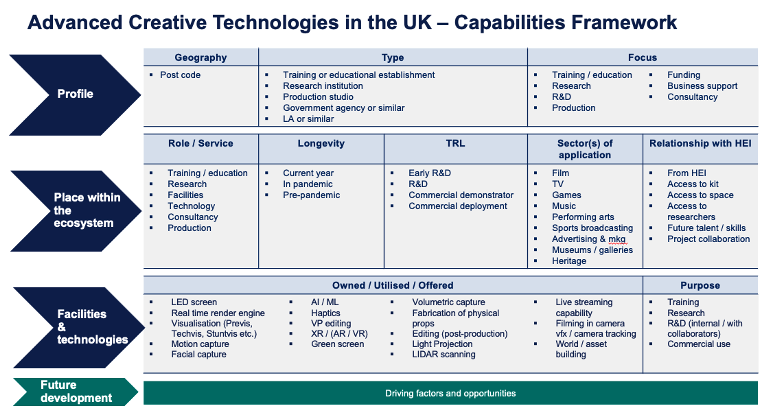

The first phase entailed the creation of a VP Capabilities Framework for capturing existing and proposed assets, or facilities, and assessing where in the value chain such assets are positioned. The second took the form of a survey to map the VP assets against the fields identified in the Framework.

Both reports can be found here.

Virtual Production

Virtual production is a way of describing a range of new production workflows and processes across TV, Film, Games, Performance and other sectors which make use of digital, spatial and other technologies. It can be defined as the use of real-time game engines and performance technologies to create a (primarily) film production process which brings together development, pre-production, production, and post-production. This site provides a useful summary with some examples of activity.

The diversity of methods and practices in the Creative Industries has previously been seen as a hindrance to scaling R&D. However, the emergence of technologies such as motion capture, spatial computing, machine learning, and real-time rendering offers the potential to seamlessly integrate production processes from concept to final product in the Screen sector (including Film, TV, and Gaming) and Performance sector (including Music, Theatre, and Events). This ‘virtualization’ of production, made possible by the combination of these technologies, has the potential to significantly increase productivity and create the next generation of entertainment experiences, while also offering new opportunities for researchers in arts, humanities, and other fields working with these technologies.

In the case of film, VP is starting to change how films are made, with actors being directed on set in conjunction with a real-time and computer-generated environment. This production methodology incorporates technological advances in game-engine, machine-learning, camera tracking techniques, and merges virtual and augmented reality, computer-generated imagery, and visual effects. In games production, the advent of engines that generate real-time visuals has already been transformational and the interested reader is referred to the Epic Games’ VP field guide report.

Given the levels of activity and innovation taking place, an overview of the VP landscape within the UK is overdue.

Framing the challenge

The research questions addressed in the first phase of work were:

- What are the key characteristics of the VP landscape in 2022, in terms of geography and in terms of research, innovation and commercialisation?

- As a fast-emerging and dynamic network of resources, technologies and processes, what taxonomy can be devised to help track this development over coming years?

Addressed at a relatively superficial level, the first challenge implies a mapping of assets to assess the scale of activity, the geographical spread or intensity, and the type of activity. The second challenge acknowledges that any mapping exercise will be imperfect, since it is based on what is an emerging and rapidly evolving set of activities.

This research aimed to map the emerging landscape for Virtual Production in the Creative Industries, both in terms of geography and ‘technology readiness’. As a short piece of work, operating across a very fast-moving set of creative technology practices post-pandemic, the ‘map’ or ‘maps’ created were always intended to be snapshots of a dynamic landscape; and the more substantial outcome of the work would be the creation of a Framework, which might form the basis of a programme of future research.

Through a combination of Data-gathering and Mapping, Literature Review, Workshopping, an Expert survey and interviews, the research team undertook an iterative exercise of building, developing and refining a data-capture Framework for this dynamic area of Creative Industries development.

- Literature Review: Given VP is a combination of techniques and technologies (eg. visualisation, performance capture, game-engines, etc), we identified recent academic papers in each of them. This involved a key word search and an extensive survey of recent literature cited in the documents above. This helped to provide insights into some of the key technologies being deployed, which informed complementary work packages.

- Mapping Framework: A Mapping Framework, through which we could begin to capture and segment data to be gathered, was generated through a half-day brainstorming exercise. The aim was to design and iterate a framework for the capture of data which could be used to generate geographical and other visualisations on VP assets across the country.

- Data Mapping: This entailed a process of data-capture and mapping of existing data on VP, using the framework established above. These were iterative and closely-related processes, with the first iteration undertaken through the workshop.

We used web search to find existing VP studios and to gather information regarding technical capabilities, R&D capabilities, particular technologies, and sectors of focus.

This process was intended to help us construct a prototype of the proposed VP Capabilities Framework, drawing on already existing data-sets.

- Expert Survey: This short survey was prepared based on the insights from the data-mapping and informed by the literature review. The survey targeted at a small number of leading practitioners aimed to provide expert input into the questions generated from the workshop and initial data-mapping. The former had started to identify gaps in our knowledge which we wanted to tease out further; the literature review had helped us define some of the technologies being deployed.

- Framework re-design: Drawing on the survey and additional expert input, a process of Framework re-design was the final stage – including the design of a Survey, to generate new data and to enable the ongoing refinement of the Framework.

As a result of this work, a new definition was arrived at:

Virtual production is the use of game engine and performance capture systems to create a real-time production process which brings together development, pre-production, production, and post-production.

A key conclusion from this exercise was that what was required was not a Mapping Framework but a ‘Capabilities’ Framework. The original ambition had been to create a framework that allowed for capture primarily of geographical location and of R&D-status or Technology Readiness. Although these were vital components, it became clear that other factors – such as technologies being deployed, or commercial access – were equally important in driving the nature and scale of R&D activity.

The resulting VP Capabilities Framework is presented below.

Phase 2 – survey

The Framework informed the development of a Survey instrument which was deployed alongside the promotion and engagement activities undertaken by the AHRC as part of the CoStar application process (CoStar is a major new investment programme which will entail the creation of a national network of Creative R&D labs and facilities in screen and performance).

Although somewhat limited in scale and focus, the Survey has enabled a mapping exercise which provides a baseline overview of the VP landscape in terms of the geographic distribution of assets, organisation type, facilities offered, the technologies at stake, and capabilities, as well as the connections between assets and their relationship to different creative industry sectors.

As can be seen from the full report, this research exercise – undertaken in collaboration with BOP Consulting – has captured many of the leading organisations operating in the field, and our maps provide an emerging picture of the VP landscape by displaying the geographic distribution on the territory. The study signposts strengths and opportunities, and will help inform support strategies which aim to foster wider and more advanced industry use.

Key findings:

The current ecosystem has grown quickly (accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic), and geographically around existing creative industries clusters. It is relatively healthy and diverse, operating at different technology advancement levels, within a variety of creative sectors.

This study suggests that technology sophistication is not the central condition nor the starting point for the advancement of the field. A wider adoption of the various technologies associated with VP seems to be more important. This is connected and can be facilitated by easing accessibility and affordability to technologies and facilities.

- The geographic distribution of organisations operating in the field largely reflects the Creative Industries clusters in the UK: London and the South East have the highest concentration of VP assets.

- The majority of organisations at Technology Readiness Level (TRL) 9 are based in London which is also the region that hosts organisations across all TRLs.

- There are two main types of organisation occupying opposite sides in the value chain: the ones focused on training, education, and research (55%) and the ones focused on production – companies, studios and technology (39%).

- Organisations undertaking R&D and those at TRL 9 use and own the widest range of technologies.

- Most TRL 9 organisations own the technologies that comprise what is currently named virtual production: LED volumes, real-time render engines, in-camera VFX, visualisation and editing technologies.

- An important proportion of organisations operating in the VP landscape (33%) do not have in house facilities.

- Most organisations operating in the VP field offer training and education.

- There is a strong established relationship between the industry and HEIs.

- Affordability and access to kit seem to be what is slowing down a faster and wider adoption of VP.

A more exhaustive study into the VP ecosystem in the UK that builds on these findings, especially including more large commercial studios, will be beneficial. It would help test and strengthen this baseline and confirm some of the hypotheses, especially around TRL typologies. Repeating it periodically would allow a close monitoring of development and a targeted allocation of resources.

Key insights

Reviewing research and data captured across both reports, and reflecting on insights being generated from other CRAIC research (for example on Advanced Creative Technologies and on Festivals and Live Experience), we would identify the following as key findings, which are worth highlighting here:

- Research lags behind industry practice in this area. New studios are continually being built, new productions are deploying new technologies, and new training courses are being developed and launched. It will take 2-3 years before the research on these catches up.

- Unsatisfactory terms are being used to capture trends in industry activity – ‘CreaTech’ being the most obvious, which is not an industry term but rather borrows from wider rhetoric commonly used over the last ten years, for instance FinTech, HealthTech, GovTech etc.

- Any useful definition of developments in creative technology must be based on a structured understanding of the particular creative technologies involved and how they are driving transformation of production, consumption and distribution in the Creative Industries. This continues to be a focus for CRAIC research.