Professor Andrew Chitty, Loughborough University London, and Creative Economy Champion for the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Hidden among the various Covid-investment measures in the recent Budget announcement was the announcement of a review of the R&D Tax Relief scheme – including a review of definitions and eligibility. This has been a long-standing issue for many in the Creative Industries – a sector which can feel misunderstood by government and struggles to align with pre-existing industrial definitions and policies. At present the R&D Tax Credit is currently only available to some sub-sectors of the Creative Industries, and there is a long-held view that the current interpretation is restrictive – thus reducing potential investment in R&D for the Creative Industries.

This essay considers

- The current operation of the R&D Tax Credit framework in the UK

- The role that a refreshed framework could play in encouraging R&D in the post Covid-19 recovery of the Creative Industries

- Whether there is a role for UKRI in supporting change to the current system of operation.

The current operation of the R&D Tax Credit framework in the UK

R&D tax credits are a tax relief designed to encourage greater R&D spending, leading in turn to greater investment in innovation. As such, they form a central part of the Government’s commitment to increasing R&D spend to 2.4% of GDP – confirmed recently in the publication of an R&D roadmap at the end of 2020.

The Tax Credit system works by either reducing a company’s liability to corporation tax or by making a payment to the company. Small or medium-sized enterprise (SME) R&D tax relief allows companies to:

- deduct an extra 130% of their qualifying costs like salaries and software from their yearly profit, as well as the normal 100% deduction, to make a total 230% deduction

- claim a tax credit if the company is loss-making, worth up to 14.5% of the surrenderable loss.

In addition, an R&D expenditure credit can also be claimed by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) who have been subcontracted to do R&D work by a large company or who have received a grant or subsidy for their R&D project.

The credit is calculated at 13% of a company’s qualifying R&D expenditure and is taxable. Depending if a company is profit or loss making the credit may be used to discharge the liability or result in a cash payment.

In all instances the activity must meet the government’s definition of R&D which is currently:

A specific project to make an advance in science or technology. It cannot be an advance within a social science – like economics – or a theoretical field – such as pure maths. The project must relate to a company’s trade – either an existing one, or one that you intend to start up based on the results of the R&D. To get R&D relief a project must have:

- looked for an advance in science and technology

- had to overcome uncertainty

- tried to overcome this uncertainty

- could not be easily worked out by a professional in the field

A project may research or develop a new process, product or service or improve on an existing one.

Latest data from the government shows that the amount claimed by companies is growing year-on-year. In 2017-18 (the latest year for which we have complete figures) the total number of claims for R&D tax credits was 62,095, claims from SMEs accounted for 54,005 of those. The total amount of R&D support claimed was £5.1bn in 2017-18, against a total value of R&D expenditure of £36.5bn.

The Case for the Creative Industries

A recent Policy Briefing from the Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre has suggested that the specific definition of R&D Tax Credits adopted by HMRC restricts the ability of certain sectors in the Creative Industries to claim the tax credit. At the core of this issue is the requirement for the R&D to be in service of ‘scientific or technological advance’ and that ‘Science doesn’t include work in the arts, humanities and social sciences (including economics)’. Many CGI/GFX, animation, computer games and companies across the wider digital creative sector make significant use of this tax relief (perhaps more than is commonly recognised) but the ‘creative’ development expenditure of Television and Film production companies does not qualify. R&D in the Design sector may sit somewhere between the two based on recent case law (see below).

Sector bodies have sought to make an extension of the R&D Tax Credit part of wider post-pandemic recovery efforts. This would not only address the apparent market disadvantage for creative businesses compared to other sectors, but also help put the UK on a level playing field with international competitors. The changes needed to bring about a growth in R&D are not radical or contentious. Simply put: a less restrictive interpretation of existing definitions would unlock a wave of investment. This would provide a boost beyond the creative industries which would aid economic growth beyond Brexit and the Covid pandemic.

Research by OMB for DCMS in 2020 showed that though only 14% of the Creative Industries consider themselves to be conducting R&D that fits within the HMRC definition and claim R&D Tax Credits accordingly, by contrast, 55% can identify R&D activities under the Frascati definition.

An extension to the eligible sectors and activities to encompass content and IP producing companies (like those in TV) would offer rapid financial relief to a range of businesses across the CIs.

Reframing the definition

The case for reframing the definition formed the basis of a more extensive research report from Nesta in 2017.

(Proposals from Nesta in 2017 to modify the definition of R&D)

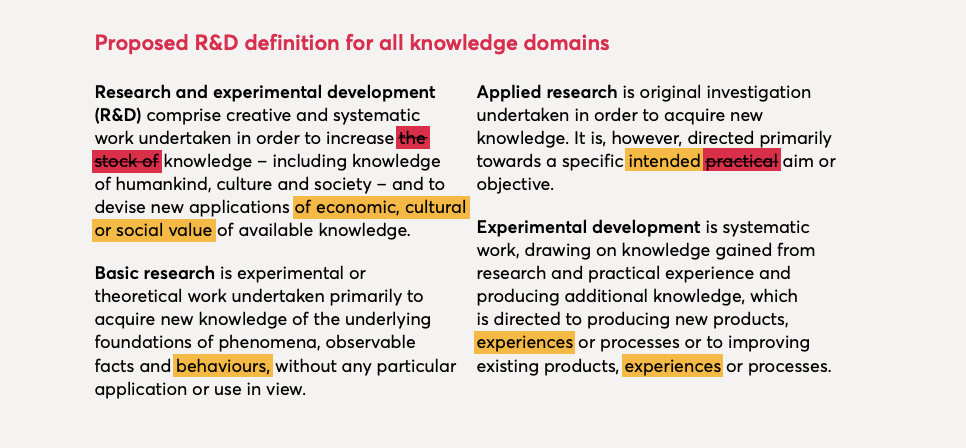

HMRC’s definition is much more restrictive than other international definitions such as the OECD’s Frascati Manual (“Research and experimental development (R&D) comprise creative and systematic work undertaken in order to increase the stock of knowledge – including knowledge of humankind, culture and society – and to devise new applications of available knowledge”) which not only extends the concept of R&D to applications of knowledge from the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences but also defines the framework of Basic Research, Applied Research and Experimental Development that underpins both UKRI’s grant funding across its nine councils and the block exemptions within the EU State Aid Framework that apply to R&D.

The Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre has also complained about the unfair disadvantage faced by UK business scarred by Covid. “The definition of R&D used by HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) for the purpose of tax relief excludes the arts, humanities and social sciences. This is in contrast to many other countries like France, Italy, Demark, Czech Republic, Brazil and Korea. This means that R&D in the creative industries which is more reliant on the arts, humanities and social sciences is not recognised and often fails to qualify for R&D tax-relief.”

Maximising existing incentives

Notwithstanding the case made above, there is clearly more that could be being done within the current definitions. The OMB research cited above notes the strong variations in awareness of the R&D relief from sub-sector to sub-sector (with 80% of IT firms aware of the scheme, but only 32% of Design companies and less than one in five Music, Performing and Visual Arts companies).

The government’s 2005 Cox Review of Creativity in Business recommended that the existing definition be flexed to enable Design to be encompassed. In 2006, Nissan’s Design Unit won a tax relief claim against HMRC for design work dating back two years, working with Deloitte to demonstrate successfully that design process costs can be eligible for tax relief within the current definitions.

If there were a greater level of awareness among businesses and a more flexible approach from the Treasury, perhaps creative businesses could be reaping greater returns from the current regime.

The need for a more flexible approach from the Treasury on Tax Credits should also not divert attention from the fact that direct public funding for Creative Industries R&D lags behind other sectors. Our own analysis of Government data suggests that whilst 28% of the R&D spend of the Life Sciences sector is provided by Government Funding (£3bn public R&D spend vs £7.5bn industry R&D spend on sector GVA £16.7bn) only 6% of Creative Industries R&D spend is supported by government (<£100m public R&D spend vs c£1.5bn industry R&D spend, on sector GVA of £111bn).

Parity

Nonetheless, there is a strong case to consider developing new ways of framing the argument for extending the eligibility for the tax credit. Redefining R&D to include the entirety of the creative industries is a pathway to fairness and parity with other allied fields, and it would match the approach to R&D in other countries.

AHRC, through UKRI, could use its considerable convening power and intellectual leadership to reframe the debate about R&D in such a way that puts culture and humanities on a par with science. Cultural IP could be considered as much a driver of advanced economies as science, and a refashioned R&D Tax Credit regime could enable support for the risk of developing and applying new knowledge to the production of new forms of IP. It’s a debate worth having – and one between equals in an economy that relies on culture and science together to set a path for future growth.

April 2021