By Professor Chris Speed, Chair of Design Informatics, University of Edinburgh

The term ‘imaginaries’ is often used in the social sciences to describe a meaning system that frames individuals’ lived experience of an inordinately complex world. This paper reflects on the extent to which design has the capability to disrupt imaginaries about the flow, representation, and production of value, through the development of products to assist people to construct new socio-economic imaginaries. It builds upon Bob Jessop’s inquiry into “how can we develop distinct patterns of material practices and material cultures that are transformative and lead to development and not merely quantitative growth?” (Jessop 2013, 9′ 10″).

The paper uses a workshop method to explore socio-economic models in order to better balance the multiple imaginaries that participants hold with the opportunity to design disruptive and critical propositions. Reflections upon the workshop and the concept of imaginaries allows the authors to identify a challenge for design in which it must accept its role as a mediator of value. In this sense, it may well be useful to deploy the concept of ‘socio-economic imaginaries’ in thinking around creative research and innovation, as a method of understanding the different ways in which creative businesses generate value from their experimental activity.

Defining Imaginary

The word ‘imaginary’ has become a useful term to encapsulate both the way that people sustain a model of the world, but also provide clues to the challenges that design research faces in revealing norms and hegemonies that define social practices within society. Toward the latter part of the twentieth century, social scientists began to use the term ‘imaginaries’ to supersede the concept of ideologies that were associated with political and religious principles. In Studies in the Theory of Ideology (1984), John B. Thompson describes imaginary as “the creative and symbolic dimension of the social world, the dimension through which human beings create their ways of living together and their ways of representing their collective life.” Manfred B. Steger and Paul James (2013) define imaginaries as the “patterned convocations of the social whole. These deepseated modes of understanding provide largely pre-reflexive parameters within which people imagine their social existence-expressed, for example, in conceptions of ‘the global,’ ‘the national,’ ‘the moral order of our time’.”

Bob Jessop (2012) understands the imaginary as “a semiotic ensemble (or meaning system) that frames individual subjects’ lived experience of an inordinately complex world and/or guides collective calculation about that world. There are many imaginaries and most are loosely-bounded and have links to other imaginaries within the broad field of semiotic practices. They exist at different sites and scales of action – from individual agents to world society (Althusser 1977; Taylor 2004). Without them, individuals cannot ‘go on’ in the world and collective actors (such as organizations) could not relate to their environments, make decisions, or engage in strategic action. In this sense, imaginaries are an important semiotic moment of the network of social practices in a given social field, institutional order, or wider social formation (Fairclough 2003).”

Meaning making and structuration

Simply put, imaginaries are a way of describing the meaning systems that frame our lived experience through habits, routines and beliefs, that allow us to ‘go on’ in a world that is full of complexity (Jessop, 2013). In his 2013 lecture, Jessop extends the complexity of social imaginaries by describing the different entry points and standpoints that allow people to ‘go on’ in an ever increasingly complex world: selective observation of real (natural and social) world; reliance on specific codes and programmes; use of certain categories and forms of calculation; sensitivity to specific structure of feeling; reference to particular identities; justification in terms of particular vocabularies of motives; efforts to calculate short to long term interests.

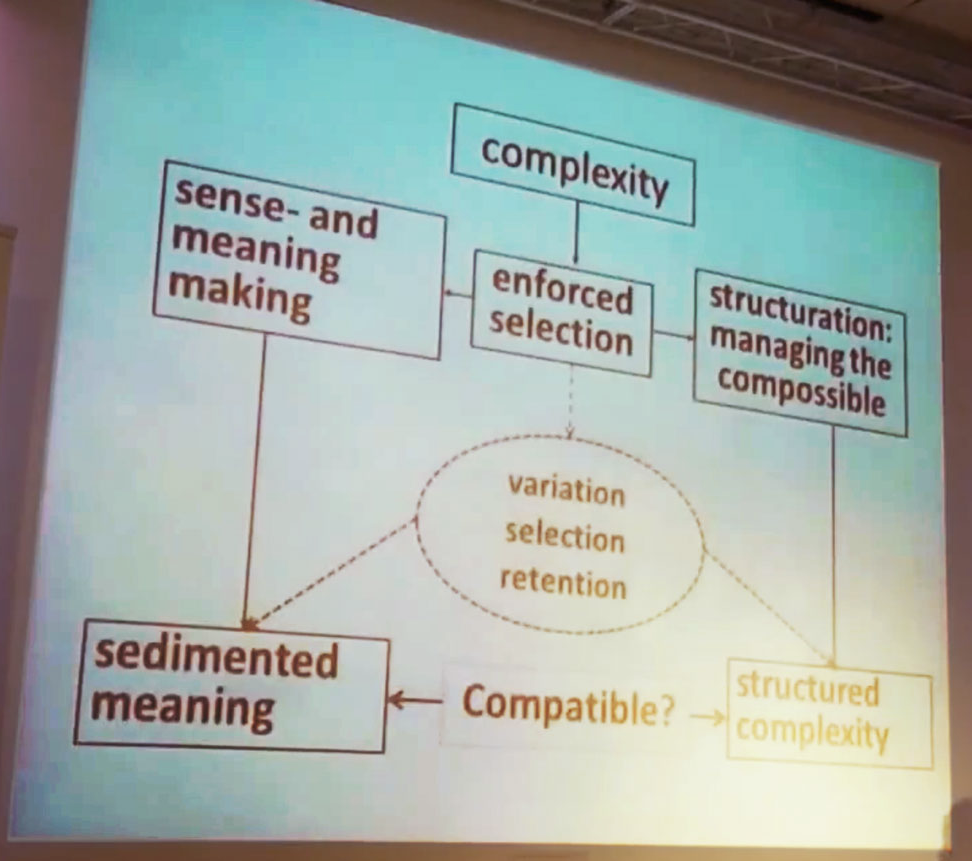

Jessop goes on to use the diagram below (Fig. 1) to describe the apparent tension between semiosis (‘sense and meaning making’) and ‘structuration: managing the compossible’. Describing semiosis as “an umbrella concept for all forms of the production of meaning that is oriented to communication among social agents, individual or collective;” whilst, “structuration establishes possible connections and sequences of social interaction (including interaction with the natural world) so that they facilitate routine actions and set limits to path-shaping strategic actions.” (Jessop 2013 16’ 27’’)

It is (arguably) across these tensions that design finds its fiercest challenges. On the one hand, providing products within services that offer insight and critical sensibilities for making sense of the world at large (contributing to semiosis), and on the other fuelling the market with products that allow people to ‘make do and get by’ without worrying about everything (contributing to structuration). Jessop questions ‘are these activities compatible’ from a human perspective? For people who ‘use’ designed solutions, compatibility is simply a way of finding the right tools, products and services that correspond to how they have made sense of the world for as long as they have been within it (sedimented meaning). This suggests that however unethical and unsustainable a product may be, people will find a way to make it compatible with their imaginary in order to ‘go on’ in the world. Following his explanation of the tension that occurs between semiosis and structuration, Jessop describes the contested nature of imaginaries suggesting that: “Imaginaries are not pre-given mental categories but creative products of semiotic and material practices that have more or less performative power.” (Jessop 2013, 23’42”)

For designers who provide products and services, we might ask, whose imaginaries do we think we are offering products and services for? And furthermore, when is it possible to commensurate the two drivers of semiosis and structuration?

Designing new economic imaginaries – GeoCoin Cinema workshop

Of the many imaginaries that we share, economics and the flow of value are complex and highly uneven according to the distribution of wealth. With a view to ‘brokering’ new economic imaginaries, members of the Centre for Design Informatics developed a workshop that empowered participants to design how the flow of value took place across smart-contracts that were deployed in the street. To do this, the team developed a piece of software that runs in the browser of a smart phone, that allows participants to script GPS coordinates with simple economic rules: if somebody enters these coordinates debit their account, if somebody enters these coordinates credit their account etc. The economic zones can be easily administered through a web interface, allowing workshop organisers and designers to quickly set up new experiences alongside participants (Nissen et al, 2018). Following a short ‘body storming’ experience in the street based upon the scattering of coins by workshop leaders, participants are invited back to the workshop to design their own economic settings that function according to the deployment of smart contracts. After identifying a context and an ‘imaginary’ in which social practices are influenced by a socio-economic model in which value flows between actors depending upon their actions, participants are asked to use simple cards to plan out the rules for why money should be deducted or gained. Based upon an adaptation of the simple logic ‘If This, Then That’ the cards prompt participants to decide on how they should deploy the GeoCoin smart contracts across the local area.

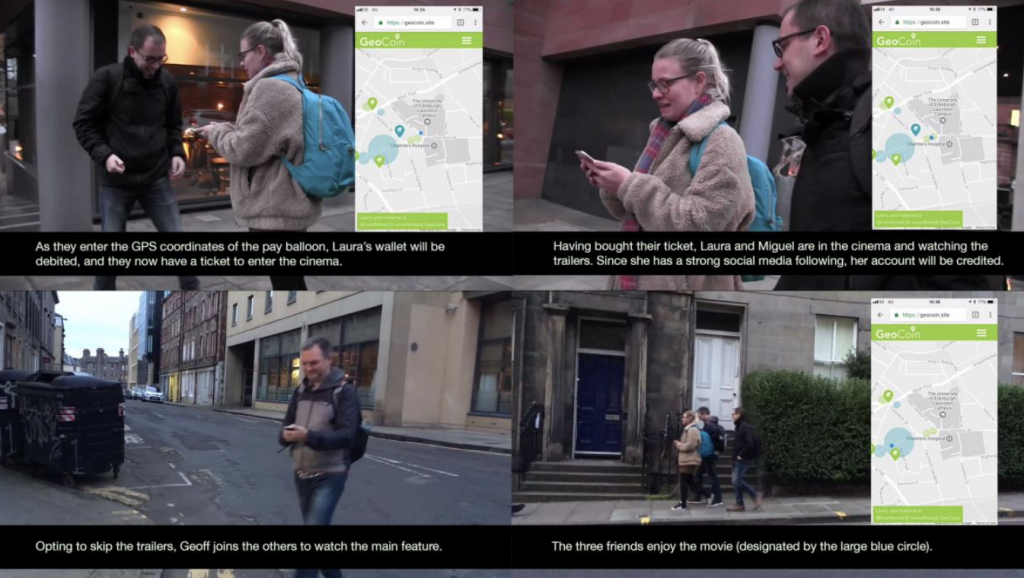

The workshops end with the deployment of the rules into the software platform and participants moving outside in order to ‘practice’ the imaginary. Screen captures from the video (Fig 2), show three participants taking part in a GeoCoin workshop who have ‘re-imagined’ an economic model for experiencing the cinema. The GeoCoin workshops synthesise the complex nature of smart contracts and provide a platform through ‘body storming’ that allows participants to use them to develop novel imaginaries. Whilst it is probably too ambitious to suggest that the practices of participants in the GeoCoin workshop have ‘sedimented’ to form any robust new economic imaginaries, it is interesting and indeed exciting to see how participation in the design of new digital systems is able to lead to conversations in which both the representation of value transcends simply money and that the flow of value is explored across multiple actors, and correspondingly their multiple imaginaries. The authors would suggest that the combination of body storming that enabled participants to ‘embody’ digital economic transactions, and their empowerment in the design of an economic system, contributed to a synthesis of both semiosis and structuration, to form a new economic imaginary – one in which participants attain the agency to balance economic value with the social, environmental, and cultural values.

Designing value – the role of design as a mediator

No longer are designers simply contributing to stages in a value chain as a product moves from manufacture, packaging, distribution to consumption; designers are retained to mediate the value of products and services within a complex network of social and environmental connections. Coined by Normann and Ramirez (1994), the term ‘value-constellations’ describes the economic systems that emerged at the end of the 20th century as globalisation and new technologies influenced the way that value was sustained. Recognising the role of co-created value within networks, Normann and Ramirez highlight that “successful companies conceive of strategy as systematic social innovation: the continuous design and redesign of complex business systems” (1994). Where once there were value chains – and therefore clear points at which ethical solutions might be embedded – there are now complex networks within which value is created, distributed and co-constructed in ever-changing ways.

Within a value-constellation, the value of a service is constantly mediated according to the flows of data that allow users and stakeholders to sustain the value proposition associated with a product, service or experience. These more dynamic models of value creation and relation represent a different opportunity for design to retain a relationship with users throughout their engagement with products (Speed & Maxwell 2015). Value constellations allow designers to anticipate and respond to shifts, identify opportunities, and understand social practices. Such opportunities require a reframing of what designers think they are designing—not products, not services, but the propagation of value and new socio-economic imaginaries.